AS de-industrialisation strikes at the roots of Britain’s once distinctive industrial character, thousands of citizens have begun to look back nostalgically on an age of skill and simplicity which they feel has been lost; or worse, taken from them.

They collectively reminisce about a time in which towns and cities were famous for what they produced.

This is the first paragraph of a thesis which is an account of research carried out by local historian Stephen Rodwell, which I thought I would share with you this week.

With the somewhat esoteric-sounding title of ‘Post-industrialism, Single Industry Regions, and Identity: High Wycombe – Furniture Town’, it nevertheless contains some interesting observations on our town.

As examples of these ‘single industry regions’ Rodwell quotes Sheffield which prided itself on its cutlery industry; Coventry on the manufacture of automobiles; and High Wycombe, once the capital of the British furniture trade and, before that, the centre of the manufacture of chairs in the Western world.

The thesis uses High Wycombe as a case study of the processes involved in the construction and successful deconstruction of these single industry towns. It asks, and answers, the question of why High Wycombe continued to prosper through this transition, while others have struggled.

In the 18th century, London was the centre of the furniture industry, with craftsmen like Chippendale and Hepplewhite establishing prosperous firms which designed, made and sold fine furniture, including chairs, to furnish the great houses of Britain. But only 30 miles away on a main coach road was High Wycombe, surrounded by hills where beech trees grew abundantly, and elm and ash were also available.

These materials were ideal for making the simpler chairs which were required for the servants’ quarters of the great houses and for the smaller houses of the expanding middle class. Entrepreneurs, such as Samuel Treacher and Thomas Widgington, spotted this opportunity and established the first chair-making businesses in the town.

From these early beginnings, the chair-making industry spread throughout the area. In a census taken in 1798, a total of 60 men were listed as chairmakers, by far the largest single occupation other than agricultural labourers and servants.

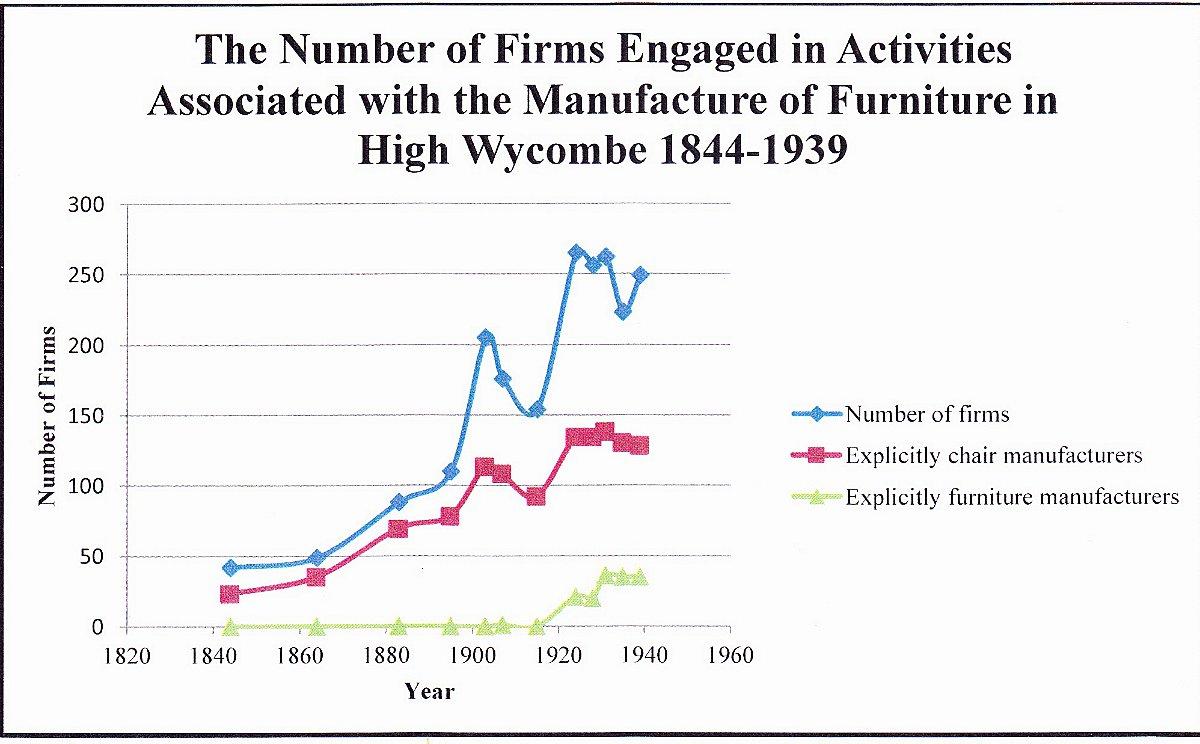

A trade directory of 1823 lists seven master chairmakers, and five cabinetmakers and upholsterers. By that time, of course, the ‘bodgers’ would have been turning chair components on their pole-lathes in the beech woods. The number of firms engaged in chairmaking grew steadily to about 110 at the outbreak of WWI in 1914. After the war, growth was resumed to a peak of around 140 firms when WWII began. In this inter-war period, the industry diversified into more general furniture-making, with around 40 firms so engaged by 1939.

Figures for the number of firms in the industry are not readily available post-WWII, but the number of people employed therein peaked at about 10,000 in 1955, declining to c.6,000 in 1975. Today the number can almost be (proverbially) counted on the fingers of one hand!

What are the reasons for this decline in Wycombe’s furniture industry?

Rodwell’s thesis offers three main reasons:

- Competition from international competitors in an increasingly globalised industry.

- Decentralisation, whereby many furniture manufacturers have chosen to relocate their factories to more attractive locations. In several cases, these relocations have been within the county – both Ercol and Hypnos (which was formed as a result of the integration of GH&S Keen and WS Toms, both High Wycombe firms) moved to Princes Risborough.

- Diversification of Wycombe’s occupation base.

But the population, and prosperity, of the town has continued to grow. The reason for Wycombe’s continued success economically is the diversification of employment opportunities.

As pointed out in Rodwell’s thesis, this process began during World War II, when Wycombe was declared as a ‘safe haven’ for people and industry. Being only 30 miles from London the town attracted a large number of new companies from the capital. Engineering, in particular, became a major industry, taking up 29 per cent of the available factory floorspace in 1945 compared to 13 per cent in 1939.

Over the same period, industrial floorspace for furniture manufacturers declined from 71 to 35 per cent. The industrial estate at Cressex, which began to be developed in the 1930s, was a major driver of this diversified industrial growth. The M40 motorway also played a big part.

By 1982 engineering firms employed over 9,000 people, the largest category in Wycombe. Since then employment in the town has reflected national trends, with a shift from manufacturing to service-based occupations. By 1991, banking and finance employed 16 per cent of the total population, the third largest employer.

I am grateful to Stephen Rodwell for allowing me to quote extensively from his thesis, which was submitted for a First Class Honours degree in History from the University of York. To consult the thesis email stephenrodwell1@gmail.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here