THIS week we continue our WWI theme and the important roles which women played during the conflict.

So far we have considered their contribution on the Home Front, in the factories and the shops, now we look at how women were more directly involved, as nurses.

There were two types of nurses in WWI: Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD), who were unpaid volunteer nurses. Because they were unpaid they tended to come from the higher class where money was not an issue, although there were many exceptions.

These nurses were often members of the Red Cross and were given basic medical training. Their job was to give comfort and simple medical treatment to injured soldiers in hospitals. The hospitals were either in the war zone or back home in England.

First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) nurses had a much less glamorous job.

Their role was to disinfect the rooms where injured soldiers had been, attend to the hygiene of the soldiers, and remove the bodies of those who had died for burial. They also drove ambulances and ran soup kitchens and general canteens.

Both VAD and FANY nurses could also be found on the trains or ships being used to transport soldiers.

The VAD organisation was founded in 1909 with the help of the Red Cross and order of St John. Each individual volunteer was called a detachment, or simply a VAD.

There were some 74,000 VADs in the country at the outbreak of the war. The first VADs went to France in September 1914 under the leadership of Katherine Furse. She was then appointed Commander-in-Chief of the VAD.

Female volunteers over the age of 23 and with more than three months’ hospital experience were accepted for overseas service.

Many VADs were decorated for distinguished service. Among the VAD nurses who achieved fame after the war was Vera Brittain, who told of her experiences in her best-selling novel Testament of Youth published in 1933.

Others included Hattie Jacques and Agatha Christie, who had several VAD characters in her books.

The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry was founded in 1907 by a Captain Edward Baker. His idea was that women who joined FANY would not only be first aid specialists, but also have skills that would be useful on the battlefield itself.

The early members of FANY were trained in cavalry work, signalling and camping. The Royal Army Medical Corps, unlike many of the senior politicians and in the military, recognised the valuable role that women could play and helped in training recruits to FANY.

Following the outbreak of the Great War, the FANY nurses soon demonstrated the value of the work they could do, by travelling to Belgium.

After only six weeks FANY nurses were working at a hospital in Antwerp. At the end of October a group of them went to Calais, where they set up a hospital in a convent to care for wounded soldiers who were waiting for evacuation back to England.

By the end of the war FANY nurses had been awarded 17 Military Medals, 27 Croix de Guerre and one Legion d’Honneur.

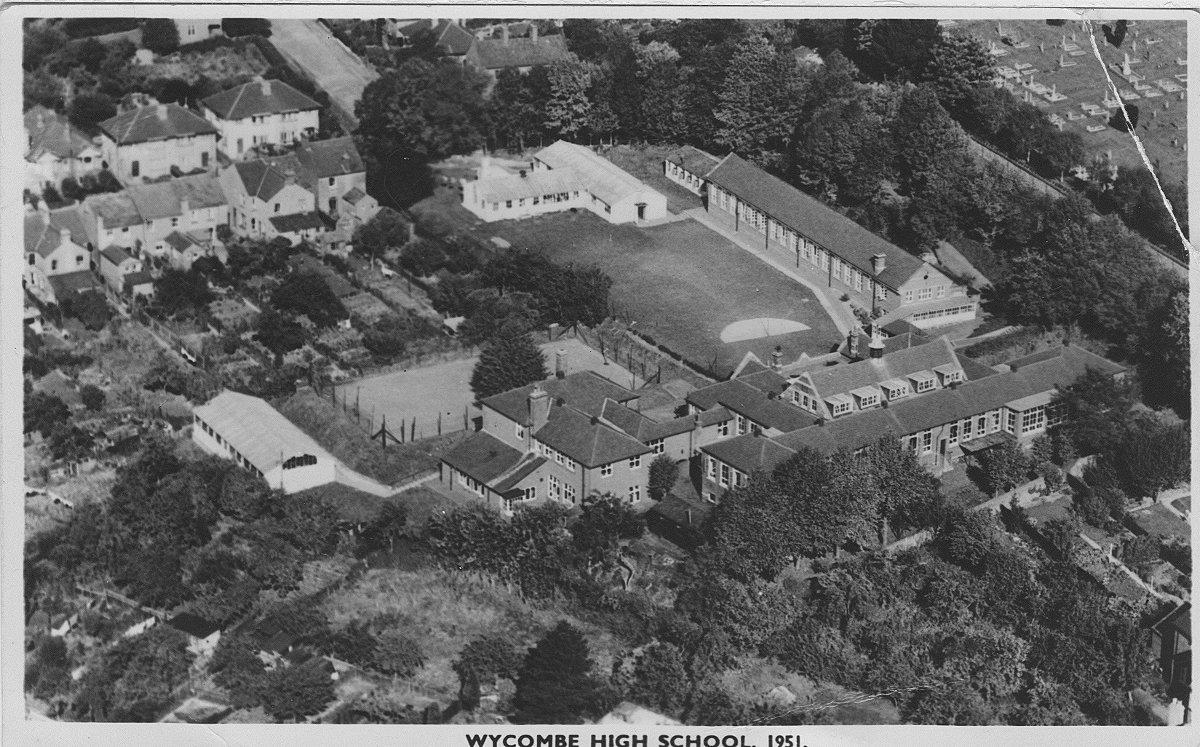

In High Wycombe a VAD hospital was established at the beginning of the war.

For this the buildings of the High School in Benjamin Road were taken over, and on December 1 1914 the school moved to two houses in London Road.

These were within a few minutes walk of each other, Oxcroft House and Bedford House, which is where the private school Crown House is presently located.

The school magazine at the time stated “Of course, we feel somewhat cramped in our new quarters, and we have no room large enough to be used as a general assembly hall; but we are glad to be able to do something definite to help in the national crisis. We hope the sick men will be happy in the old school, and soon get well and strong again.’’ Apparently this move was intended to be only temporary, and the school moved back to Benjamin Road in June 1915.

Presumably the authorities believed their own rhetoric, and thought that the war would be over quickly.

But in November 1915 the War Office asked for the school premises again. This time the school moved to the old Royal Grammar School buildings in Easton Street.

The school could not have foreseen that it would be nearly another four years before they were able to return to their old premises.

The school magazine reflected their pleasure at returning ‘’Now the war is over, we have at last, to the great joy of everyone concerned, gone back to our old school. Ever since the Armistice was signed, we have been longing to return. At Whitsuntide [which would be in 1919] we had a week’s holiday, while the old building was being prepared and arranged.’’ During the four and a half years when the VAD hospital was open, around 3,500 wounded soldiers were treated, not all surviving of course.

In 1916 the average number of patients per day was 63, increasing to 90 in 1917 and c.100 in 1918. In 1916 a total of 834 patients were treated, and 1,044 in 1917.

Such an increase required temporary buildings to be erected in the grounds. These were referred to in an article in the Bucks Free Press on August 12 1918 which read: “There was an unfortunate outbreak of fire in the grounds of the VAD Hospital on Sunday evening, when one of the large marquees, used for sleeping purposes by the patients, was practically destroyed together with its contents.

“The outbreak was discovered about 5.45pm, and the flames quickly spread, burning beds and mattresses and the patients’ lockers and belongings. Fortunately none of the patients were in the marquee at the time, otherwise the result would have been more serious... The Volunteer Fire Brigade was not summoned to the scene, as the outbreak was soon extinguished by the men at the hospital.’’

No doubt the residents of the town responded to the soldiers’ lost belongings with their usual generosity by quickly replacing them. Practically every issue of the BFP would have a list of the items which had been donated to the soldiers in the VAD hospital, with of course the names of the donors.

To be continued...

I am grateful to the Archives Office of Wycombe High School for allowing me to study their records relevant to the school's use as a Military Hospital, and also for allowing the use of the photograph of Nurses and soldiers inside one of the wards.

- FEEDBACK - That’s my mum I can see in your featured photograph

Reader Mrs Thelma Styles has been in touch in response to the appeal with the article in the edition of February 14 for information about the factory workers assembled behind a two-bladed aircraft propeller.

Thelma recognised her mother Rebecca Ford, always known as Dolly, who is the young lady third from the right in the first standing row of the picture below. To her right is Olive Rolfe, and in the back row second from left with a moustache is Fred Pearce.

The photograph was taken outside the factory of William & Herbert Giles in Church Lane, West Wycombe, which later became the location of the chairmakers E.M.F. Brown which you can see far right.

The other picture is looking south down Church Lane, West Wycombe, 1911. The factory of William & Herbert Giles is on the left.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here