The Amersham anti-slavery petitions of 1824 and 1830 (Nostalgia 13 November 2020) are important evidence of the grassroots abolitionist movement that persuaded the government to end slavery in the British colonies in 1833.

Voices of black people in the community also played an important part in the struggle particularly through the eyewitness accounts of former slaves like Olaudah Equiano and Mary Prince. Their autobiographical accounts of the horrors of slavery were publishing sensations and widely read.

After 1833 the abolitionist movement continued to campaign against slavery elsewhere in the world and particularly in North America. This time formerly enslaved African American men and women were at the fore of the crusade, travelling to every corner of Britain to inform people of the true nature of slavery. Frederick Douglass is the most famous black abolitionist of this period, but around 7 years before he arrived in Britain, Moses Roper was already lecturing and touring in South Bucks.

Moses Roper was born enslaved in North Carolina around 1815. When he was 7, Roper and his mother were sold to different masters. He was subsequently resold several times. He frequently ran away, but he was always captured and violently punished. Finally, in 1834, he escaped on a ship which was headed for New York.

By late 1835, however, his fear of being recaptured grew so intense he decided to leave America for Great Britain. In Liverpool, Roper presented a letter of introduction to British abolitionists, who warmly welcomed him. They provided him with an education at schools in Hackney and Wallingford before he attended University College London. In 1837 he published his own account of his experiences as a slave and toured from Penzance to Inverness giving lectures on the horrors of slavery. In 1839, he married an Englishwoman from Bristol, Ann Stephens Price. In 1844, they sailed for Canada and had 4 daughters. Roper returned to Britain for further lecture tours in the 1850s and 1860s, giving around 1000 lectures here.

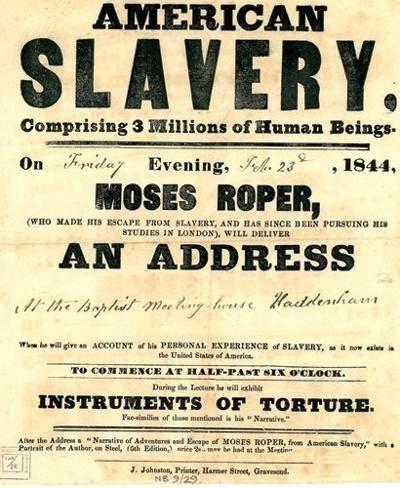

Between 1838 and 1844 Moses spoke in many of the towns of Buckinghamshire including Marlow, High Wycombe, Beaconsfield, and Chesham. He also toured smaller rural communities such as Chenies, Little Kingshill, Speen and Great Missenden. The Bucks Archive recently found a promotional poster advertising a talk at Haddenham Baptist Meeting House. He relied on local religious circuits, particularly Quakers and non-conformist ministers, to arrange and advertise the lectures and provide him with transport, and hospitality.

His talks were well attended and widely reported in the local press. Described as “very tall and athletic looking” by one writer he did not hold back on brutal descriptions of his experiences. He exhibited whips, chains, and other gruesome instruments of torture such as the “paddle” which resembled a cricket bat with holes in it. He described how after one escape attempt, he was tied to a bale of cotton, and then beaten with the paddle until he was covered in raised welts. His owner then sawed these open with a fine saw! Such graphic descriptions were too much for some who discredited his testimony. Moses refused to moderate his language however and insisted he would tell the truth of his experience.

Later, abolitionists confirmed his experiences. In August 1854, John Brown, another escaped slave spoke at the Temperance Hall in Chesham. According to the local paper, Brown “delivered a very thrilling lecture, dressed in horns and bells, as worn by recaptured slaves”. He also sang African hymns to entertain his audience but didn’t hold back from graphic description: “he recited the sufferings he endured under the hands of Dr Hamilton who practised upon him by way of experiment and put him into a burning hot pit dug in the earth, almost depriving him of respiration to test his strength of constitution!”

Born enslaved in Virginia, John Brown also made several escape attempts before he was successful, eventually settling in London in 1850, where he found work as a carpenter. He also contacted the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and started to lecture around the country. He was illiterate but dictated his memoirs to the society’s secretary who published them in 1855. He later married a local woman and earned a modest living as an herb doctor. He never returned to America and died a free man in 1876.

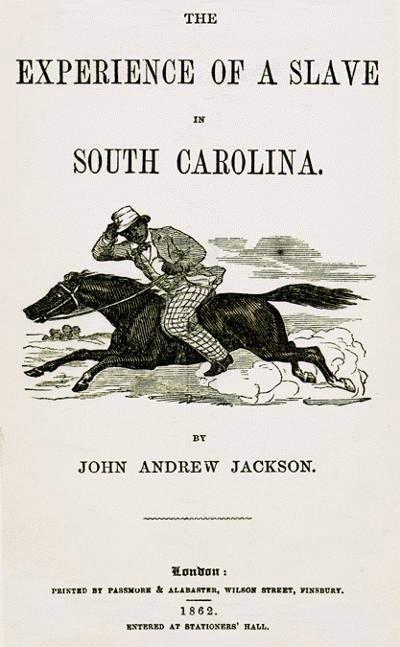

In April 1861 just after the start of the American Civil War, John Andrew Jackson, another fugitive, gave a talk at the Temperance Hall in Chesham. The War had reignited interest in American slavery, and abolitionists wanted to convince the British public to support the Union (anti-slavery) cause. Unusually Jackson was accompanied by his wife Julia who often gave her testimony of life as a slave. She is believed to be one of the first African American women to talk publicly about her experience.

John Andrew Jackson also recorded his memories and spared no details in relating the murder of his sister, and his frequent whippings at the hands of a “Christian” master and mistress. After he was separated by sale from his first wife and children, he escaped on a pony he had exchanged for 3 hens before stowing away on a ship bound for Boston. He initially settled in Canada where he met Julia, a fugitive slave from North Carolina.

With the support of Harriet Beecher Stowe the Jacksons travelled to Britain in 1857 to raise money to purchase the freedom of John’s children. With the end of the Civil War they returned to live in Massachusetts. A longer version of this article can be found at amershammuseum.org.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here