Home ownership was rare in the early 20th century, when 90% of householders were tenants. Housing became a hot topic during the first world war when it was reported that the army had to reject many potential recruits due to poor health caused by insanitary living conditions.

Then when the war was over soldiers who had risked their lives for their country would be returning to the same overcrowded and unhealthy accommodation. This would not be “the homes fit for heroes” promised by the government.

Living conditions in 1918

Like most towns, High Wycombe had families living in unacceptable conditions. The worst dwellings were in the area to the west of the town centre known as Newlands. This was eventually demolished as part of the government’s slum clearance programme, but not until the 1930s. It.is now the location of the Eden Shopping Mall.

In Newlands the tenements had no mains water, gas or electricity. Author Charles Rangeley-Wilson* has described the area thus “In Newland the houses were packed closely together, row on row, with only alleyways, lanes, or courtyards between them. Damp and cold in winter, and stinking all through the summer, these houses were built on marsh-land that hardly drained. Drinking wells and hole-in-the-ground privvies might flood into one another with just the smallest lift in river height, during “February fill-dyke” for example, or when the caning girls threw all their cane-shavings into the river and blocked its flow [the river was the Wye]. Each privvy was shared by up to fifty people, and if not holes in the ground or boxes in sheds, they hung off the backs of houses suspended over the stream or its ditches...”

The 1918/19 flu pandemic had only exacerbated the issue. The lack of decent housing was debated at local council meetings, For example at Amersham it was reported in June 1920 that “in the recent influenza epidemic 89 per cent of the deaths occurred in houses where the housing conditions were bad”.

The 1919 Addison Act

In 1919 Dr Christopher Addison became the Minister for Health in David Lloyd George’s post-war coalition government and it was his responsibility to fulfil Lloyd George’s pre-election pledge to build ‘homes fit for heroes’. Based on architect MP Sir John Tudor Walter’s report on social housing, the 1919 Housing and Town Planning Act was a radical piece of legislation.

The report set the standard for much of the housing built in the 20th century. It detailed how spacious housing, with proper sanitation and individual bedrooms could be built cost effectively and therefore offered at affordable rents. If a tight rein was kept on construction costs and the houses conformed to the five types recommended in the Tudor Walters report, building schemes would be generously subsidised by the Government. This heralded the beginning of Social Housing in this country.

How Wycombe Councillors Re-acted

In Wycombe, the council submitted outline plans for four new housing schemes to the Ministry of Health, these were in Wycombe Marsh; Terriers; Hughenden Valley; and Hampden Road. An inspector from the goverment’s Housing Commissioner “visited the Borough to confer with the District Medical Officer of Health” in mid-December 1919 when the sites were visited.

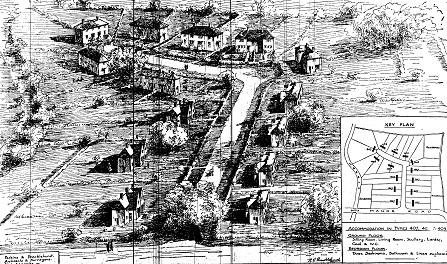

A scheme for 100 houses in four different styles at the Cock Lane site was approved at the January 1920 Council meeting. The Terriers scheme for 106 houses was approved at the meeting in February, and a new site at Copyground Farm, between Desborough Ave and Copyground Lane, was agreed for consideration.

The proposed scheme at Hughenden Valley was on a site of about 35 acres, part of the Hughenden Manor estate owned by Major Coningsby Disraeli, who had offered to sell the site to the Town Council. Because the site was just over the boundary of Wycombe parish into Hughenden parish, permission to develop the site was required from Wycombe Rural District Council and Hughenden Parish Council, neither of whom objected. The plan was to get the parish boundary of High Wycombe extended to include the site.

However it was not until May 1921 that a special meeting of Wycombe Town Council met to make a decision. During the meeting a useful summary of the present situation for housing requirements in Wycombe was provided by the chairman of the Housing Committee.. He said that a total of about one thousand new houses were required, of which only about 200 had so far been approved, at the Wycombe Marsh and Terriers sites. At the Marsh site after 12 months only 4 houses had been completed, mainly due to trade union interference in calling men out on strike.

The Hughenden scheme was for 200 houses, but at a high cost of £10,000 for the site “which was more than they ought to pay”. After a 2.5 hr debate the Council voted 15 – 11 not to proceed with the Hughenden scheme.

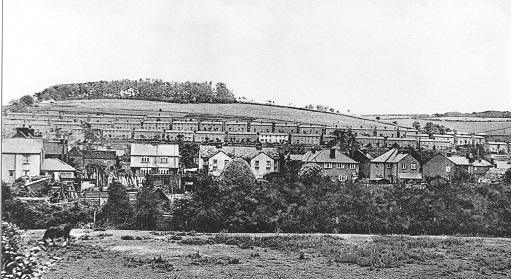

The schemes at Terriers and Wycombe Marsh were eventually completed. The latter became known locally as Tin Town due to the unusual construction method employed.

Private Enterprise Takes Over

Later in 1921 the government withdrew all state subsidies for the construction of new houses, schemes approved before July 14 1921 being allowed to continue with the subsidy.

In 1923 a new subsidy scheme was introduced, but based on a fixed amount of £6 per house for a 3 bedroom house, or £8 for a 4 bedroom one.

This grant was paid per annum for 20 years. This subsidy scheme was aimed at private builders but local authorities could apply for the subsidies, although they still had to raise the capital themselves.

The following year this new scheme was improved, the grants increased and the period over which they applied extended to 40 years. There was a sting in the tail however as the rents charged by the council could not add more than £4.10s. on the rates. This was to ensure that the housing built was cost-effective.

In 1925 the Hughenden Park scheme was resurrected, but on a smaller scale, by builders G H Gibson & Sons. Thirty houses were built, of three different designs but all having the same floor space and “gas, electric light and a town supply of water” were all laid on. In 1926 the houses were offered for sale, with freehold ownership, at £600 each. Wycombe Rural District Council offered, under the Housing Act, mortgages up to £475. The estate is now known as Manor Gardens.

In 1926 the grants were reduced, to nearer the 1923 levels. This had little effect as the building programmes were now in full swing and gathered pace in the 1930s. The demolition of the Newland’s slums was among the schemes in Wycombe, the residents being re-housed at Castlefield.

Charles Rangeley Wilson is the author of “Silt Road, The Story of a Lost River”, the river being the Wye. The book was published in 2013 and reviewed in the Bucks Free Press.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel