With many thanks to Martin Pounce, the producer of the Amersham Martyrs Community Play, for contributing this article and for the lovely illustrations.

An essential part of preparation for the play always involves research to help the cast visualise the early Tudor community in which the play’s events took place. We have looked to see what buildings standing in Amersham today might have existed in Tudor times and we came up with a longer list than you might expect. John Leland, an English poet and historian, wrote in 1541 that “Amersham (also then known as Hagmondesham) is a very pleasant town with a Friday market, and a single street of good timber buildings”. There are some existing buildings which would have been standing when Leland passed through. We know that the museum building at 49 High Street dates from around 1480, just before the Tudor period. Much of the original timber structure of the roof above the central hall, the carved arch-braced truss, and part of the solar wing can still be seen. But what happened to the others? It turns out that many Tudor buildings have survived – but they are hiding!

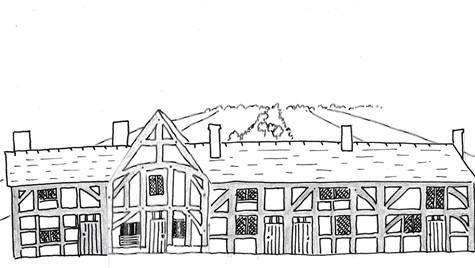

To the casual visitor, and even some of the guidebooks, Amersham looks like a Georgian town with its brick terraces lining the High Street and Whielden Street. Nearly all these brick facades disguise earlier timber-framed buildings. A row of cottages (84 to 92 High Street) on the south side of the High Street towards Shardeloes, was re-faced and extended at the front by about 4 feet in 1807. The then lord of the manor, Thomas Tyrwhitt-Drake, had recently purchased the cottages to add to his extensive property portfolio, as he already owned most of the houses in Amersham. He was responsible for disguising many of the timber-framed houses behind new brick facades. The brick frontage was built to give the original assortment of houses a uniform terrace appearance and to conform with the taste of the period.

These renovations are commemorated on the back of no 86 with a plaque which says ‘TDTD 1807’ and the letters stand for Thomas Drake Tyrwhitt-Drake, the squire’s full name. The backs of the houses were also given a brick skin, evidenced by the iron tie bars which hold the brick to the main wooden beam. Whilst researching these houses, Martin found original bills for the building work in the Drake Archives in the Bucks Archive Collection. When he unfolded them, it was clear that he was the first person to look at them since they were bundled up 200 years before! A bill from James Maycock for employing bricklayers 29 June – 11 July 1807 came to £10 9s 7d.

Hidden in this row of cottages is however a much earlier Tudor timber-framed ‘hall house’ predating the other cottages and probably built around the same time as the Amersham Museum building. This would have originally stood on its own burgage plot. In 1200, after the Earl of Essex had bought the right to a weekly market and an annual fair in Amersham, the South side of the High Street was laid out as a planned town with burgage plots 440 ft long extending to a back lane, the Common Platt. These plots were offered to ‘burgesses’ – bakers, butchers, drapers, tailors and other useful tradesmen and craftsmen to encourage them to settle in Amersham.

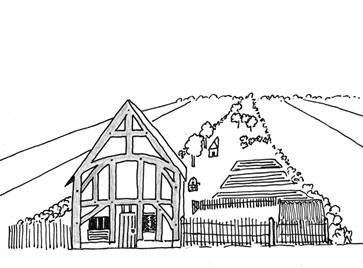

The original house comprised a hall at the rear of the current house open to a crown post roof and a gabled solar (the family’s private living accommodation) facing the street. Initially the house would not have had a chimney. There would have been a hearth in the middle of the floor with smoke allowed to escape through gaps in the roof. There was no upstairs window as there was no upper floor, at this stage. There might have been a platform accessed by a ladder. Young women who failed to marry were ‘left on the shelf’.

The front of the property would have been fenced to stop animals being driven to market straying from the road and a pig would have probably been kept in a fenced enclosure. Behind the house there would have been vegetable beds to grow beans, peas, carrots, parsnips and pulses (no potatoes, which were introduced from the Americas 100 years later). There were fruit and nut trees and fruit bushes. The family would have kept hens, mostly for their eggs but old hens which had stopped laying would end up in the cooking pot. To the left of the door the window would have had a shutter that dropped down so that resident could sell his produce and craft work on market day.

In the late 16th a floor was inserted making the hall two storeys. About the same time fireplaces and chimneys would have been added. When Tyrwhitt-Drake refaced the row of cottages in 1807 the gabled front of No. 86 was lost to create the uniform appearance of the terrace, and the sawn off rafters can still be seen in the roof space. Strip away the brick skins along the High Street and you will still find Leland’s “single street of good timber buildings”.

Amersham Museum reopens tomorrow, 19 February. Please visit to see how our original Tudor ‘hall house’ evolved over the centuries and to purchase your tickets for the Amersham Martyrs Community Play in March.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here