This article was originally published in the newsletter of the High Wycombe Society and the author Mark Page has kindly allowed it to be republished on the Nostalgia page in a slightly modified form.

Mark and his friend Andy Aliffe have a comprehensive collection of coins and tokens relating to High Wycombe, which includes an unusual aluminium token. At the instigation of Jackie Kay of the High Wycombe Society, who enquired about the token’s meaning, they decided to research that further. This is what they discovered.

In the year 1932, Wycombe found itself grappling with a daunting challenge: widespread unemployment. The root of this issue lay in the advent of new industrial processes, which systematically replaced the manual craftsmanship that had once thrived in the local furniture industry. As the winds of change swept through, many hundreds of skilled furniture makers found themselves without jobs. This, together with a similar number of other workers, was a significant blow to the community, given that the entire population of High Wycombe hovered around 26,000 souls.

Although the government’s unemployment benefit scheme, which had been introduced in 1920, and known as the dole’, provided relief to some families, this did little to help the general population in the long term. The relief was limited to 39 weeks, and from 1931 the amount paid per week was cut by 10% and was means-tested.

The officials who carried out these tests were often seen as insensitive, and many families were offended. The test created many problems for families.. Those with some savings or a small additional income had their dole reduced. Tensions were caused because, if an older child had some work, or a mother had a part-time job, or a grandparent was living in the house without paying rent, the Means Test could result in dole being refused. Heirlooms and items such as pianos had to be sold and savings spent, before the dole was received.

Prominent citizens act

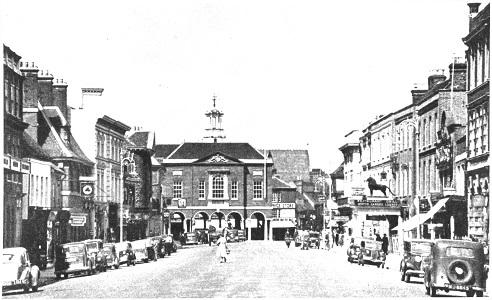

The distressing situation, however, ignited a spark of resilience in the hearts of several prominent individuals within the town. Determined to mitigate the impact of the growing unemployment crisis, they banded together. On December 14 a town hall meeting was convened by the High Wycombe Rotary Club, and nearly a thousand concerned citizens gathered to deliberate and craft a solution to this pressing issue.

Among the attendees at the Town Hall were notable figures, including Reverend W.L.P. Float, President of the Rotary Club, Councillor W.S. Toms, who held the office of Mayor, Mr. J.L. Humphrey, Councillor W.H. Healey, Councillor G.H. Brocklehurst, and Alderman W.H. Tyzack. The keynote speaker was Sir John Foster Fraser, a well-known travel writer and journalist, who was one of the most well-travelled men of his time. He had visited some 54 countries before settling down in Princes Risborough.

In his introductory remarks the Chairman of the meeting Cllr Toms gave the up-to-date figures for the number of unemployed in the town - furniture trade 400, building trade 254, engineering 33, various 184. A total therefore of 871. He then explained that the Town Council had drawn up a long list of works that needed to be done, and in order to help reduce the un-employment all tenders would contain a clause specifying that 90% of the labour involved must be local.

In a very stimulating speech Sir John Foster Fraser focussed on the two issues which he proposed would greatly alleviate the unemployment situation. These were the need for people to actually spend some of the money tied up in their savings, and for those who were in-work to provide assistance to those who were not. His closing statement was ‘Let your slogan in High Wycombe be “Do it now! Then long before Spring comes the sunshine of brotherhood will have driven away the black shadows of unemployment in this town.”

Wycombe Work-Finding Committee

This gathering was followed by a business meeting at the Rotary Club at which Mr Lucian Ercolani, Chairman of the Rotary Community Service committee proposed that a General Committee should be established ‘for the purpose of forwarding a scheme’. This was agreed, and was to be called the ‘Wycombe Work-Finding’ (WWF) committee, with the Mayor as Chairman.

No time was wasted in arranging for the WWF to meet, doing so on December 19 at the Guildhall. On behalf of the Rotary Club Mr Ercolani suggested two possible schemes, one a general appeal to find work for the unemployed and the other a detailed organisation for procuring work. He proposed a target of £20,000 for new work. It was agreed to form an executive committee to pursue this, with six members, two appointed by the Rotary Club, two by the Town Council, plus the Mayor and the Secretary. This would have the power to co-opt additional members, and Mr Frank Adams was appointed. The Mayor also undertook to consider the formation of a separate Women’s Committee.

The really pivotal meeting was held in the Guildhall on January 11, 1933, by which time unemployment had increased sharply to 750 in the furniture trade and 350 in the building trade. The discussion revolved around ideas for gainfully employed people to extend a helping hand to their unemployed brethren. Suggestions ranged from refurbishing their homes and tending to gardens, to shop renovations. ‘Work-finding’ sub-committees were elected to serve each of the four wards in the town, with a secretary appointed for each: They were to arrange for canvassers to make house-to-house visits within a week to urge all residents to do everything in their power to support the schemes.

The local Chamber of Commerce and the Wycombe Branch of the British Legion had agreed to support the scheme. A Publicity Committee had been formed, chaired by Mr Reginald Rivett, the founder of the department store Murrays.

Innovative proposals

Then in the midst of deliberations, Lucian Ercolani introduced some innovative proposals that captured the collective imagination. He unveiled three exquisitely carved solid oak house nameplates, each priced at a modest 7s 6d (equivalent to 37.5p today). He envisioned the Furniture Manufacturers Federation supporting this initiative by encouraging their sales representatives to showcase these nameplates to their clientele. It was estimated that orders for 4,000 of these nameplates would generate 50 hours of work per week for 20 individuals over a three-month period. Ercolani appealed to those in attendance to serve as guarantors, pledging £75 to cover the costs of the first 400 nameplates. Mr Winter Taylor later advised that a well-wisher had granted £50 towards the costs. It was hoped to make the Wycombe-made nameplates fashionable across the country.

In addition to the wooden nameplates, Ercolani had solid silver tokens crafted, intended to serve as keepsakes commemorating the collective effort to combat unemployment. One side of these tokens bore the High Wycombe Crest, with the CHANGE IDLE MONEY FOR A BUSY INDUSTRY inscription and on the reverse PUSH THE WHEELS OF INDUSTRY ROUND 1933.

Ercolani managed to sell 20 of these silver tokens himself at £19 each, a noteworthy accomplishment. A subsequent run of aluminum tokens was produced, to be offered at a mere 2d each, with the hope of raising an additional £40. These tokens were designed to symbolize the town’s collective determination to conquer the scourge of unemployment. These tokens, particularly the silver ones, have left an indelible mark on the town’s history.

As we reflect on this fascinating piece of Wycombe’s past, we wonder: where are these tokens today, and who purchased them? And do any of the Ercolani house nameplates survive? We invite you to share your stories and connections to this historic endeavour, as we strive to add more layers to this compelling narrative. The legacy of Wycombe’s collective action in the face of adversity lives on, and your contributions to this tale are most welcome.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here